About all that…

Not surprisingly, people have been asking me for a comment about the news that Brad Lander, got busted by the New York Post for having a long list of driving infractions, which included multiple instances of speeding in excess of 11 miles per hour in school zones and parking illegally at hydrants and bus stops. Brad is my City Council member, a longtime partner in many safe-streets advocacy efforts, and has been responsible for so much that has gone right with things like bike lanes and bike share in the community and across the city, perhaps more than nearly any other elected official. He has been and still remains my number one choice for Comptroller, a position I think he was born to hold. (I was also asked to comment on the mayor’s comments in which he called Lander a “hypocrite,” but more on that later.)

I’ve been reluctant to say much on my typical outlet, Twitter, because I didn’t believe a tweet or even a tweet storm would accomplish what I felt I wanted to do, which was, of course, to condemn any form of reckless driving in no uncertain terms and to hold an ally to account, which I think is obviously the right thing to do on its face. But I also wanted to organize my thoughts, speak more directly about how it feels when an ally disappoints and offer some general thoughts about What It All Means…. especially in year eight (!) of Vision Zero.

I bulleted these out and they all kind of build on each other but might not always connect, so stick with me. And if you think I’ve missed the mark or whatever please let me know.

- Speeding is wrong. Period. I could get my head around saying this was no big deal if this involved one or two speeding tickets spread out over a year, but part of the story here is that Brad Lander racked up seven tickets in less than 18 months, according to the Post, possibly making him eligible to have his car impounded under the original version of his own Reckless Driver Accountability Act. I also don’t think parking at a bus stop is ever okay, given the amount and types of people it potentially inconveniences. I think Lander stumbled in his original response to being called out on this, most notably on Inside City Hall with Erroll Louis last night. I am glad he offered a more full-throated apology today and vowed to hold himself accountable going forward.

- When an ally messes up, it can be tempting for advocates to leap to that person’s defense, point to those who have done far worse, or use that ally’s otherwise noble accomplishments as a bit of a shield. Fear, subconscious or otherwise, kicks in: “If this person goes down, the entire cause I support could go down with him!” There are so many bad-faith people out there trying to take down sensible traffic safety measures and I understand that sort of reflexive defense. But we have to be honest when one of our own does something that jeopardizes his and possibly a movement’s credibility. There’s some other lawmaker out there with a worse record who opposes consequences for reckless drivers? Not my problem.

- Some people have said, “Hey, it’s the Post. What do you expect?” There are a lot of problems with the Post, but this story isn’t one of them. First, the reporters behind it are great. Second, wrong is wrong even if you learn about the wrong thing from a source you don’t always like. Whatever people may think of a particular news outlet, sometimes “gotcha” journalism gets ya.

- I’m speaking from learned experience here: back in 2014 when the mayor’s motorcade got caught running stop signs by Marica Kramer in a CBS-2 exclusive, my gut reaction was to brush it off and say that what really mattered was that he had just introduced Vision Zero. I bought into the idea that his position meant that his travel and security needs didn’t compare to other people’s. Fear kicked in: I was worried that a hugely important but politically precarious policy wouldn’t even have the chance to get off the ground. Plus, my thought at the time was that since Marcia Kramer was clearly someone who didn’t give a shit about safe streets the whole story was just another one of her infamous hit jobs. I even got into it with some journalists, as I recall. (Yes, dear reader, even I once defended the mayor.) But looking back, I was wrong. Today I think about it like this: If I was killed by a driver who ran a stop sign, would it be any comfort to my family that the driver believed he was important?

- Elected officials need to be held to the same standard as average citizens, if not a higher one. I don’t believe it’s okay for anyone to excuse their reckless driving or anyone else’s by pointing to their policy records, saying they have important places to be, or claiming that they have unique security concerns — as the mayor said when defending himself to Marcia Kramer. Fish rots from the head, as they say, and such excuses lead to all sorts of motorist entitlement that metastasizes far beyond the placard class. (Cyclists who have been on the receiving end of a motorist’s rage because they dared to slow them down for two seconds know exactly what I mean.)

- In Streetsblog, Gersh Kuntzman wrote that “advocates were quick to say that it’s foolish to focus on the actions of any one driver when the problem is specific roadway design and the larger culture.” It might be foolish if we were talking about John Q. Driver or Jane Q. Motorist who don’t have any direct influence over public policy, but in this case we’re talking about the mayor of New York City and a prominent member of the City Council. What elected officials say and what they do matter immensely; when there’s a gap between their rhetoric and their actions it harms the causes they support and creates a lot of frustrating and unnecessary work for advocates. Believe me, the last thing I and many other folks thought we’d have to do this week is talk about the driving record of Brad Lander, of all people, or waste any energy listening to Bill freaking de Blasio call someone else a hypocrite for their driving habits.

- As somewhat of an aside, how about the mayor’s comment about all this at his daily press conference? “Everyone who says they believe in Vision Zero has to live by it. Now, you know, we’re all humans. We’re going to make mistakes sometimes, but that’s too many to chalk up to just a single mistake, obviously. So, I’m surprised.” Sure, he says “we all make mistakes” which might lead someone to think he has finally figured out what Vision Zero is all about. But that’s not how I interpret it. Vision Zero isn’t something drivers “believe in” and “live by.” You don’t get into your car and think, “I’m going to Vision Zero today.” Vision Zero isn’t about giving motorists a pass if they “make mistakes sometimes” and shaming them if they make “too many.” It’s about the people with power — that would be the mayor and DOT leadership — building a system where the consequences of any mistake, whether it’s a driver’s first or fiftieth, aren’t deadly or life altering to anyone inside or outside of a car. Anyway, Bill de Blasio is going to leave office never having understood one of his signature policies.

- On the street design front, Shabazz Stuart pointed the discussion to larger questions about infrastructure and its influence on driver behavior. Anyone familiar with my take on Vision Zero knows that I agree with his opinion wholeheartedly — but I think we have to go one step further and question not just the conditions that contribute to reckless driving but the primacy of car culture itself. Yes, our streets are “designed to encourage driving at high speeds,” as Shabazz correctly notes, but they’re also designed to encourage driving. Full stop. We can’t uncouple reckless driving from the fact that New York City’s transportation policy is essentially, “Drive ’em if you’ve got ’em.” I received my last speeding ticket in 2004 on a trip to Virginia and my last parking ticket three summers ago when I forgot to move a rental car for alternate side parking. While I’d like to think I’ve received so few tickets because I’m the most conscientious driver in the city, a bigger reason is that I pretty much never drive. Traffic calming is necessary and effective, but I don’t think we will reduce dangerous driving in any significant fashion until we reduce driving in general.

- In order to take on the primacy of car culture in New York we need to first take on car culture’s primacy in New York City politics. As part of his vow to hold himself accountable for his actions, Brad Lander has promised to give up his placard and drive less. That’s all good, but why does any elected official even have a parking placard to give up in the first place? Why is it just assumed that they need to drive so much? Because they have important places to be and important things to do? Nope. Sorry. That’s some real tragedy-of-the-commons type reasoning, because the list of what people might consider an important trip is as vague as it is long and could apply to anyone anywhere, with devastating consequences for [waves to entire city and planet]. Why does an able-bodied person need to drive to pick up his dry cleaning a few blocks from his house? Because he’s on his way to somewhere important and anyway it was just for a few minutes? Why does someone think it’s okay to be driven to get a pastry and a coffee twelve miles from where he lives? Because it keeps him grounded and sane while doing his important job? Why do community boards get budgets for buying cars? Why does the Brooklyn Borough President continue to make excuses for using a public plaza as a private parking lot? Why do elected officials and their staffers need to drive to a City Hall that sits on top of more subway lines than exist in most of the rest of the United States combined? Because they have a lot of important stuff to do, work hard and keep a busy schedule? Bullshit. There are eight million stories in the naked city and each one of them involves people who work hard and keep busy schedules. If they all use that as an excuse to drive, we’re fucked.

- So where does this leave me? Pretty exhausted, to be honest. It’s still mind boggling that both the man who campaigned on Vision Zero and the elected official who became its biggest supporter have each been caught driving recklessly, one nearly eight years ago and the other this week. It’s almost like a perfect set of bookends to the story of New York’s version of Vision Zero itself, with the volumes in between filled with plenty of success stories, to be sure, but far too many stories of racist crackdowns on immigrant delivery cyclists, cops running over Citi Bike users for riding with headphones, the distribution of massive amounts of parking placards and PBA courtesy cards, no end in sight to the amount of parking required in new buildings, community boards spending multiple hours over multiple months debating lines of paint on a couple of streets and a pandemic-induced spike in traffic fatalities the city still doesn’t seem to know how or want to address. We have so much work to do.

Brooklyn Spoke Media

I haven’t updated the blog in a while partially because so much has moved to social media, but mostly because I’ve been focused on other projects like The War on Cars. As some readers may know, my day job for a long time has been in TV production and writing while advocacy consumed my nights and weekends. I’m now proud to announce a melding of both worlds with the launch of Brooklyn Spoke Media, my new production and communications consulting business.

If you are part of a mobility/transportation company, nonprofit or advocacy organization working to make cities better then I’d love to work with you. I’m also moving some of my public speaking engagement activities over to Brooklyn Spoke Media. My clients already include a shared scooter company, climate change foundation and more. Learn more about the business and thanks for your support!

On the Media… coverage of free parking

From James Barron’s recent piece in the Times on the possibility of eliminating free street parking:

“For drivers, finding a parking spot in New York City is already hard enough. There are so many regulations. So many hydrants. So many loading zones. And so few empty spaces. Now a local transportation committee in Manhattan has broached the unthinkable: eliminating free street parking altogether.”

Barron is connecting two very different ideas that don’t, at least in his version of things, have anything to do with each other: The lack of enough physical space for all the cars and the new (to New York, at least) idea of paying for the space that’s available. “Eliminating free street parking” is not the same as “eliminating parking.” If there’s still street parking but one has to pay for it, that would make it easier for drivers to find a spot. A city that charged for street parking could find that economic sweet spot that encourages people who don’t really need their cars to give them up, leaves enough space so that the people who do need their cars could always find a place to store their vehicle, and take whatever is left and put them to higher uses such as bus lanes, bike lanes, bike share stations, loading zones, parklets and more. Was Barron’s graf edited or checked by anyone for logical consistency before it went to print?

Speaking of higher uses, it’s worth calling out how selfish it is for drivers to constantly complain about “so many hydrants” making it difficult to find parking. It should go without saying, but hydrants exist so that if a building is burning down the fire department can put out the blaze, stop it from spreading and save lives. It’s quite literally the highest social benefit curbside space can have. We often let bellyaching about hydrants pass as just one of those things, as innocuous as someone complaining about the heat in summer, but if you stop and think about for even a second there’s probably no better example of motorist entitlement.

The Fierce Urgency of Later

Jumping off of this Streetsblog editorial about the mayor’s response, or lack thereof, to the urgency of climate change, I wanted to add a few thoughts.

De Blasio obviously thinks Greta Thunberg is talking to Trump and other people who don’t “believe” in climate change, but she’s really talking to politicians like him. This is what she said:

“You say you hear us and that you understand the urgency, but no matter how sad and angry I am I do not want to believe that because if you really understood the situation and still kept on failing to act, then you would be evil, and that I refuse to believe.”

You say you hear us and understand the urgency. This couldn’t be more clear. Thunberg aimed her speech squarely at the otherwise good people who probably identify as liberals and progressives, not the radical Republicans who are very much a lost cause. What many allegedly progressive politicians like de Blasio don’t understand is that our children and grandchildren will judge all of us, not just defiant conservatives, solely by what we did or didn’t do to fight for their future. (And ours. Climate change is killing people now.) That’s it. No one is going to erect statues to you for instituting universal pre-K in a city or on a planet that’s uninhabitable. That a term-limited, lame-duck mayor with no hope of holding higher office can’t be bolder in the face of environmental collapse and a drastic remaking of human civilization is beyond pathetic. It’s a crime against the planet.

I know, I know. Another post blasting the mayor. I get it. I’m a tough critic of de Blasio because he runs the city in which I live, a place where I’d like spend the remainder of mine and my children’s years, a prospect that seems far less likely with each new report from the IPCC. I can’t do much about Trump, Republican Senators, or oil company executives from my perch in Brooklyn, but I can press my mayor and local elected officials to do more, much more, than what they are doing now. Plus, New York is practically a nation unto itself, with one of the world’s largest economies and a population only slightly smaller than Greta Thunberg’s native Sweden. Our city, and the people who lead it, have a moral duty to rise to the level of their rhetoric and tackle this problem directly.

It’s the cars.

With my own daughter not far from starting her own middle school career and even closer to being allowed to walk and take transit by herself, the shocking news of 10-year-old Enzo Farachio’s death this week in Midwood shook me hard. But I don’t need a child around the same age to be aghast at what happened and angry about the response, or lack thereof, from City Hall. However, something about this case made me feel that even if the mayor deigned to speak up about the tragedy and the reprehensible victim-blaming that followed, what good would it do? The bigger problem, in my view, is with the mayor’s approach to making the city safer for people on foot and on bikes.

Yes, DOT has designed many miles of roadway and installed traffic-calming measures across the city to slow down drivers and give more space to pedestrians and cyclists, but there’s been a real cost to Bill de Blasio wasting his bully pulpit to talk about e-bikes, helmet laws and licensing cyclists, among other nonsense. Even when he puts the focus where it belongs on reckless driving or when he speaks up in support of speed cameras and enforcement blitzes against motorists, he misses the mark, at least when it comes to correctly applying the lessons and philosophy of Vision Zero. His is a very 20th-century philosophy that sees the key to traffic safety as just “Everyone obey the law.” This windshield perspective means that he sees nothing wrong with driving itself. Until he does, more people will die.

Let’s assume for a moment that the medical episode excuse is correct and that an investigation will, in fact, confirm that Alexander Katchaloft suffered some sort of seizure before he killed Enzo. Forget all questions of whether he was on any form of medication or had been warned not to drive by a physician, two things any investigation will also determine. The fact that at any moment someone could suffer a seizure, heart attack or even a sneezing fit while operating a car or SUV and crash into a sidewalk, killing a 10-year-old boy or anyone else in his path, shows the limitations of the American interpretation of Vision Zero. No amount of speed cameras, enforcement blitzes, or educational campaigns could prevent such an incident. Even if every driver got the message and obeyed the law you’d still have people like Katchaloft, Dorothy Bruns, and Howard Unger, the motorist who killed three trick-or-treaters (including a 10-year-old girl) in 2015 after allegedly suffering a medical episode while behind the wheel.

The only long-term and sustainable solution to preventing or at least minimizing further tragedies involves three things:

1. Reduce the amount of cars in the city and place heavy restrictions on large vehicles like SUVs and light trucks.

2. Ban cars from as many streets as possible so that people can wait for a bus or sit on a bench or walk to school or the office along a transitway, not de facto highways.

3. On streets where cars can’t be banned, use robust designs and tools like bollards to minimize the risk to innocent pedestrians should a driver crash.

4. Increase transit so that those with medical conditions and others who shouldn’t or don’t actually need to drive have other options.

Does anyone really think Bill de Blasio or really any American mayor believes in pursuing any of the above goals? Or is the only solution, like our country’s approach to gun violence, to lecture bad drivers about their behavior and prosecute those who kill while the rest of us keep our heads on a swivel, trying to anticipate when death might arrive? Is that our only defense? Do we have to accept a certain amount of collateral damage, so long as those responsible are held to account every now and then? Do we have to walk around knowing that at any time we or someone we love could be killed on his or her way home from middle school?

There’s another way. It will take breaking car culture in more ways than one.

Bikes, Buses, and Thinking Bigger

David Meyer at Streetsblog has a good rundown of the mayor’s latest comments about bike lanes and transportation on the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. I had some longer-than-tweet-length thoughts about them which I figured I’d compile into a post. Feel free to add your own thoughts in the comments.

Cyclists are not a defined or set group of people who exist separate from other New Yorkers.

When asked why there is not a commensurate bike-lane-enforcement plan to go along with the newly announced one for bus lanes, the mayor seemed to see these as completely separate issues. “We don’t have the resources to [enforce bike lanes] right now in the way I think some folks who advocate for the bicycling community would like to see,” he said. It was a revealing comment. Forget the very basic concern of whether or not people on bikes deserve a safe commute. (Blocked bus lanes inconvenience bus riders while blocked bike lanes can actually kill cyclists.) The mayor continues to see cyclists as a fixed group of people—“the bicycle community”—and not a population that can and should be cultivated and increased through policy. He’s about 20 or 30 years behind smart cities in this regard and New York City can’t afford to wait for him to catch up.

Smart leaders understand that cycling feeds transit and vice versa.

De Blasio continued his comments about keeping cars out of bike lanes and defended the limited focus on buses: “We absolutely believe in enforcement in bike lanes, but the point is this specific approach is about something vast.” This siloed view of transportation is holding New York City back.

Because de Blasio uses just one means of transportation—a car that takes him from, say, the front door of Gracie Mansion to the front door of the Park Slope YMCA—he doesn’t understand the first thing about multi-modalism, which is a fancy term for “how most New Yorkers get around.” People can be pedestrians, transit riders, AND cyclists, oftentimes on the same trip. In fact, one of the best uses for cycling in a city is for connecting to the subway or a bus. Community leaders in so-called transit deserts often clamor for Citi Bike stations since they’re a good way of turning a 15-minute walk to a distant subway station into a 5-minute bike ride. Even in transit-rich neighborhoods, bikes can help residents avoid an inconvenient subway transfer or the pain of waiting for a bus that’s stuck in traffic.

Again, Mayor de Blasio is way behind other cities here and that’s perhaps most obvious when one looks at New York’s moribund bike parking program. Try riding your own bike to most subway stations or bus stops around town and there’s often no place to lock up. It’s not just about keeping bike lanes clear; I’m not sure the mayor gets how much untapped potential there is in providing more bike parking near transit hubs. That’s perhaps related to my first point about how he sees “the bicycle community” as a fixed group of people; I’m not sure he can even imagine a scenario in which someone might take two forms of transportation to one destination.

Vision Zero is great, but it can give politicians an easy out.

New York is bucking national trends when it comes to traffic fatalities and deserves to have that achievement not just noted but celebrated. Likely because of that, one could sense a bit of frustration in the mayor’s voice as he responded to the question of keeping bike lanes clear. (“I’d also like the acknowledgement to be there that Vision Zero has been the central approach—and clearly working.”)

Here, the mayor’s comments reveal the limitations of leaning too heavily on Vision Zero. New York City shouldn’t just build safer streets because we want fewer cyclists to die. New York City should build safer streets because it wants more people to choose cycling. Unfortunately, the city isn’t building the kind of all-ages-and-ability infrastructure to make this possible. Trying to use a bike for even the most basic of trips remains incredibly frustrating and stressful for all but the most confident of riders, and even many of those people will give you an earful about how bad it can be out there.

Statistics only tell a small part of the story. One can have a city where no cyclists die or are seriously injured that still sucks for getting around by bike.

New York needs someone who thinks about transportation holistically.

The next mayor needs to go beyond the narrow focus of reducing death and injury and must include livability, efficiency, and affordability as part of the city’s transportation goals. Doing that will almost by default create a safer city.

Bill de Blasio and the Folly of “All-Of-The-Above” Transportation

Despite the subway system’s continued and rapid decline, there’s been a lot of forward movement in the world of New York City transportation recently. I’ll leave it to others to debate the finer points of the proposed e-bike legislation or just how and when the recently announced $100-million expansion of Citi Bike will happen, but my general sense is that when it comes to thinking about how New Yorkers get around there was a lot to be thankful for in this post-Thanksgiving week.

I wanted to focus on something that was buried toward the end of the piece by J. David Goodman that ran in the Times on Tuesday on the coming “clash” between City Hall and the City Council over legalizing most forms of e-bikes and e-scooters. Here it is:

Seth Stein, a spokesman for Mr. de Blasio, said: “While e-scooters are illegal under state and city law, the mayor is committed to innovation as part of his all-of-the-above transportation strategy to get New Yorkers moving again. We look forward to reviewing the proposals.”

Emphasis mine.

This was one of the most revealing comments on transportation from the de Blasio administration I’ve heard, inasmuch as it is perhaps the most succinct explanation for the mayor’s failure to tackle congestion and mobility in any meaningful way in his five years in office so far.

What does the mayor want? He wants an “all-of-the-above transportation strategy to get New Yorkres moving again.” So the good news is that he–or at least the people who speak on his behalf–has at least recognized that New Yorkers are hopelessly mired in gridlocked traffic.

Unfortunately, that’s the extent of the good news.

Simply put, “all of the above” is not a viable transportation strategy, no more than “pleasing all of the people all of the time” is a viable political strategy. In a city where space is at a premium, it can’t be. No metropolitan area in America or anywhere else in the world that I’m aware of has ever been successful at moving huge numbers of people efficiently by choosing an “all-of-the-above transportation strategy.” It’s nonsense. It’s also the exact opposite of leadership.

It is unquestionably true that when it comes to transportation, New Yorkers have more choices than ever before. On top of our existing subway and bus system, the city has (slowly) rolled out more Select Bus Service, opened (highly-subsided, low-capacity) ferries, expanded Citi Bike (without public funding), and devoted on-street parking spots to car sharing (after no small amount of community board whining). With Citi Bike set to expand to become the biggest bicycle-sharing system outside of China, as well as the imminent arrival of e-scooters, there’s probably never been a wider array of choices for getting from point A to point B, at least in recent memory. On paper, in fact, this should be a very good time to be among the car-free majority that makes New York the vibrant city it is.

But what good does that expanded menu do anyone if city streets remain choked by private automobiles either moving or stored, for-hire vehicles cruising for their next passenger, placarded vehicles parked on every flat surface, and a seemingly endless and unregulated glut of oversized delivery vans and trucks? If bike lanes become loading zones and bus lanes become de facto parking lanes for police officer’s personal cars, no amount of shared bicycles or articulated buses will make a dent when it comes to moving people through the urban grid.

And that’s why Bill de Blasio’s “all-of-the-above transportation strategy” is, now five years into his time in office, an abject and utter failure. New York City, woefully behind the world’s great cities, must move beyond this idea that everyone can get around however they choose. What New York needs is less “all-of-the-above” and more “some-of-the-above-but-mostly-no-cars.”

“All of the above” only works in situations where one person’s choices do not affect or interfere with another’s. And when it comes to transportation, choices matter. More specifically, how policy makers choose to allocate space matters.

The mayor likes to point out that his goal is to make New York the fairest big city in America. And while it may seem to fit with that goal of fairness to keep city streets open and available to everyone equally no matter how they choose to get around, all one has to do is try to move just a few blocks at nearly any time of day to know how that plays out. To paraphrase the French poet Anatole France, “The law, in its majestic equality, allows drivers, cyclists, and bus riders alike to enter Midtown Manhattan.”

Street space, like all space in this universe, is governed by the laws of physics and the constraints of geometry. If I remember nothing else from my high school physics classes, it’s that two objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time. In urban planning terms, that means that a bike lane can not occupy the same space as a parking lane. It’s a zero-sum-game.

Image via BikePortland.org and the City of Portland

Zero-sum games mean that someone, a mayor for example, has to make tough choices. A city cannot balance all modes, as that implies that all modes can find some sort of happy equilibrium on their own. They can’t. What a city can do is prioritize efficient modes to benefit the most amount of people. That starts with walking, biking, and transit and ends, way down at the bottom of the type of reverse pyramid of transportation hierarchy seen above, with using three SUVs to move one person 12 miles.

There are encouraging signs that people in positions of power are starting to get this and that ideas once seen to be on the fringe or that merely stayed in advocacy circles are breaking into the mainstream. On Thursday, bike and transit Twitter lit up when NY1’s host Jamie Stelter quoted City Council Speaker Corey Johnson as saying to a live TV audience, “I think we have to break the car culture in this city. We have to focus on bikes and the subway and other forms of getting around.” Councilmember Antonio Reynoso, a regular bike commuter who’s never shy about speaking up for safe streets and efficient transportation, could hardly contain his excitement at the speaker’s comments. Councilmember Ydanis Rodriguez has long expressed his desire to reduce car ownership in the five boroughs. (Although perhaps not as fast enough as current climate change modeling reports suggest we should.)

If that’s what these officials are saying now, they’re already a lot farther along when it comes to their thinking on private automobiles in the city than Bill de Blasio is after five years in office, not to mention many more as Public Advocate and as a member of the City Council. They’re even more evolved than where Mayor Michael Bloomberg was 2006, in the pre-JSK era, when he said, “We like traffic, it means economic activity, it means people coming here.” Thanks to some nudging from a smart DOT commissioner, he would later change his tune and eventually the city produced some of the best evidence around to show that streets for people are better for “economic activity” than streets for cars.

Despite offering a plethora of transportation choices, Mayor de Blasio has wasted the last five years because he has been, is, and will likely remain afraid of making tough choices, of telling motorists that they can not expect to drive everywhere for free, and of standing up to the police department. It is a sort of predatory delay and should be seen as a major black mark on his legacy, however he’s judged by history. It didn’t have to be this way, but thanks to him the next mayor will be starting from a huge deficit when it comes to getting New Yorkers moving again. If the city is to be able to grow and thrive, that person will have to make some very tough choices about what kind of transportation menu is available to New Yorkers. Some of the biggest items, private cars, will have to be taken off completely.

On Skillman Avenue and Community Boards in General

Jumping off of Streetsblog’s recap of last night’s maddening Queens Community Board 2 meeting, I wanted to highlight a few things David Meyer mentioned in his report. This includes former NYC DOT policy director Jon Orcutt’s comment on Twitter…

…and DOT’s statement today:

The design that was presented last night articulated our responsiveness to the top concern, which was parking loss. Over the past few months, DOT reworked the design to preserve as many parking spaces as possible, and in some instances, including in the commercial core, with no parking loss on the south curb of Skillman Ave and north curb of 43rd Avenue, respectively.

DOT always appreciates community board feedback , but considers the vote to be advisory on substantive safety projects. We will review our options for moving forward and continue the dialogue with the Board and other local stakeholders about making these streets safer for the local community and all Queens residents who use these corridors to shop and commute.

DOT’s statement is good, but here’s the thing: It should come before the meeting, not after. To be fair — and as their statement says — when it comes to this particular project, DOT has bent over backwards to accommodate the board’s parking concerns. As much as I think reducing on-street parking should be a longterm policy goal of the city, if the politics of doing so preclude making our streets safer immediately there’s nothing wrong with making concessions here and there to get projects in and done.

But the bigger problem remains. It’s something that I’ve seen time and time again as a public member of my own local community board and an occasional attendee at board meetings in other neighborhoods. Too often, DOT reps go to these board meetings seeking a resolution in support of their plan. Up/down. Yes/no. That’s a recipe for scenes like last night. It allows for the binary decision-making power unelected community board members currently hold and leads to a handful of parking-obsessed know-nothings having control over the entire city’s transportation network. Unfortunately, by going along with this process, DOT cedes most of the battle, so to speak, before it’s even begun. And so it takes months if not years to make any sort of progress, if it’s made at all.

The commissioner and the mayor need to change the formula. They need to send the very talented and experienced members of DOT’s bike- and pedestrian-safety teams to these meetings and allow them to begin their presentations by saying, in one form or another, “We are not here to debate whether or not we are going to fix this street. We are here to seek your input on some of the finer points of the plan, such as where you think loading zones should go, if there are any places that may require extra signage or markings, and if there are other locations where safety remains a concern. While we will take constructive suggestions and appreciate the board’s institutional knowledge and local expertise, we will not entertain any ideas that involve not moving forward with the project.” That’s how it would work with a new water main and that’s how it should work for safe streets.

Since board votes are advisory only, this is ostensibly the current formula, but for far too long it’s been allowed to be hijacked by the types of avid motorists and car storage fetishists who populate the average community board roster. It’s a vestigial process left over from the JSK years when a lot of these street designs were new and unfamiliar, at least to people who never seem to go anywhere outside of New York or, if they do, learn anything while they’re there.

DOT needs to reclaim the planning process from the beginning and not have it be held up like this. Major reform is needed, but all it would take is a strong opening statement.

Where Do All the Cyclists Live?

In previous posts, I’ve documented the language used by people who oppose bike lanes and safe streets projects. From “I like bikes, but…” to “This isn’t Amsterdam,” there are a host of things people say repeatedly in service of preserving parking and the car-dominant status quo.

And while these statements were covered in local news outlets, they didn’t originate from reporters’ pens; they were things that came out of the mouths of bike lane opponents themselves. But one thing that I’ve been cataloguing for quite some time — and least in my mind — is in fact something that comes straight from members of the press: the question of who reporters define as members of “the community.”

Take this story from the Queens Times Ledger about a revised proposal to install protected bike lanes in Sunnyside:

The original proposal by DOT, heavily opposed by the community, eliminated up to 158 spaces in exchange for bike lanes, while the new proposal eliminates 117 and 129 parking spaces on both Skillman and 43rd Avenues combined between Roosevelt Avenue and Queens Boulevard.

The original proposal was “heavily opposed by the community,” yet guess who showed up to see the new one?

The auditorium at PS 150 40-01 43rd Ave. was packed to standing room with bicycle advocates associated with Transportation Alternatives, which fights for safer streets, and community leaders such as Patricia Dorfman, executive director of the Sunnyside Chamber of Commerce, who claimed many small businesses feared going out of business entirely.

This was only the latest example of something that plays out in press coverage all over the country. When it comes to covering the ongoing shift from car dominance to people-powered transportation, “the community” is just shorthand for “people who oppose change.” People who support street redesigns, however, aren’t members of the “community.” They’re merely “bicycle advocates” or “cyclists.”

Last year, I noticed this report from Cambridge, Massachusetts:

The first public meeting on a Cambridge Street separated bike lane project drew some 150 cyclists, street residents and concerned business proprietors and others Tuesday, and the design – shifting the bike lane between parked cars and the curb – and summer timeline were received with overwhelming support.

“Street residents” tells us something useful about the people who attended the meeting, namely that they live on the affected street or at least in the immediate vicinity. Similarly, “concerned business proprietors” paints a mental picture of local mom-and-pop store owners. But who are the “cyclists” and where do they live? Your idea is as good as mine.

Here’s another example from St. Paul, Minnesota.

https://twitter.com/mikesonn/status/853948852164071424

This headline raises a good question: do any of the neighbors have neighbors who bike?

It isn’t just reporters and editors who fall into this trap. Here’s a listing from a 2017 event hosted by Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer.

Brewer has been generally supportive of bike lanes, a car-free Central Park, and safe streets in general. But the above shows that even those with the best of intentions can divide people into limited and unhelpful categories. Note the copy that asks, “How can we accommodate more bikers, and improve biker/community relations?” This makes it sound like bikers are an invasive species infecting the urban ecosystem. The listing might have been improved if it said, “How can we accommodate the growing number of New Yorkers who bike and improve conditions for all street users?”

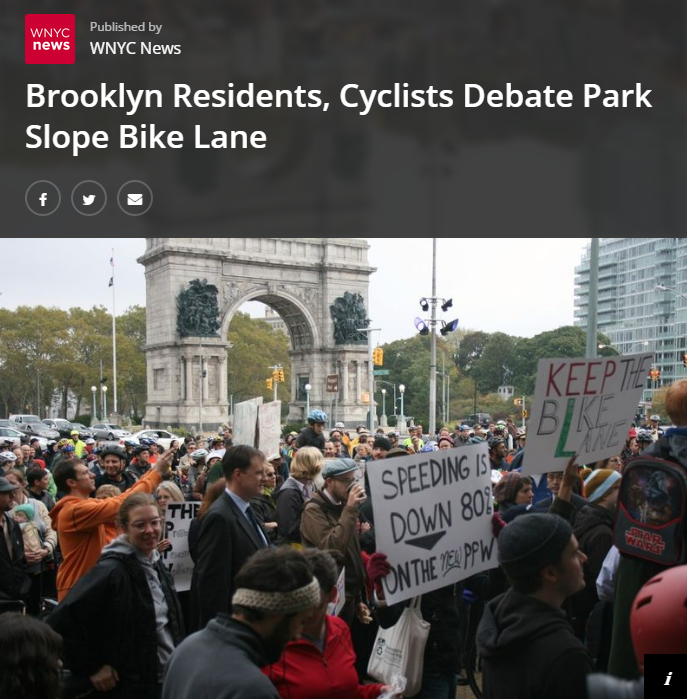

Of course, nearly every bikelash trope can be found in the case that perhaps kicked off the phenomenon, or at least elevated it to its most absurd zenith: the Prospect Park West Bike lane. Here’s how a 2010 story from WNYC framed the players in this neighborhood drama:

Some Park Slope residents believe that the bike lane has made the street more dangerous, since pedestrians now have to cross a two-way bike lane and then a one-way street when leaving Prospect Park. Some residents also say that cyclists do not obey traffic lights along Prospect Park West.

However, cyclists and other supporters said it’s not a pedestrian safety issue, since cyclists should still obey traffic lights, and pedestrians simply need to look both ways before crossing. In addition, many believe slower traffic is an improvement for a street known for speeding cars.

Now it is true that not all people who bike through a neighborhood live there, and in the case of Prospect Park West — a street that runs next to Brooklyn’s biggest and most popular park — that is most certainly the case. But that’s just the nature of city living. Most New Yorkers do not live on limited access cul-de-sacs or within gated communities. The streets that make up one neighborhood are merely threads that connect the entire urban tapestry. And that is what gives this city — any city, really — its vitality.

On a personal level, my commute to work takes me from my apartment in Park Slope and through Gowanus, Boerum Hill, and downtown Brooklyn before I reach the Manhattan Bridge. In Manhattan, I ride through Chinatown, Little Italy, Soho, and Greenwich Village. And even though I don’t reside in these neighborhoods, that doesn’t mean I’m not a member of the community of people who make up each of those places.

Sure, people who live in a particular area generally have a much more vested interest in what happens there than those who merely pass through, and local residents’ should be allowed to have a voice — but not necessarily a veto — on street-level changes. But automatically excluding or othering people simply because they ride a bike makes no sense, even if it does make for convenient “both sides” reporting. Besides, something tells me that if a group of people who lived outside a neighborhood but who regularly drove through it came to a meeting to object to a bike lane project, very few of the similarly car-dependent local residents would object to their support. And no one in the press would describe them as “avid motorists” or “car advocates.”

One reason I disdain the term “cyclist” — and the broader “cycling community” — is because it creates an artificial tribe where none really exists. Jonathan Maus of BikePortland.org shares my point of view and articulates it in this post quite nicely:

As many of you know, I have a big problem with labels like “cyclist community.” What even is that? Am I member? Are you a member? Or are we just regular people who want safer streets? Even though KPTV doesn’t use the label with any intended malice, I firmly believe labels like this are unnecessary and harmful.

Labels are lazy. They allow us to paint with a broad brush instead of taking the time to speak in more detailed strokes. Labels assume a large group of people share the same motivations and beliefs when in fact no such common cause exists. Labels also perpetuate hate and divisiveness by serving up a tidy basket for people’s anger. Labels are linguistic punching bags — a conveniently gift-wrapped “other” served on a platter for people to take swings at.

I am not a cyclist. A bike is just a tool I use for getting around. And only then some of the time. I’m frequently a straphanger. More often than not I’m a pedestrian.Occasionally I’m a driver. I guess you could call me a multi-modalist. But I think it’s easier, more accurate, and more productive to just call me a New Yorker.

Lifehacker

I recently had the chance to talk about all things bike with the good people at Lifehacker for their podcast, The Upgrade. I’m in the latter third of the episode, discussing bikelash, and why sharrows are terrible among other subjects. I also answer listener questions on everything from why all cyclists appear to be scofflaws and whether or not to go blinky light or steady beam. Eben Weiss, of Bike Snob fame, and Rosemary Bolich of We Bike NYC, are also on the podcast and I enjoyed every minute of everything they had to say.

Thanks to hosts Alice Bradley and Melissa Kirsch and producer Levi Sharpe for having me on. Please give the episode a listen and let me know what you think.